Reviewed by Raymond Friel in Markings 29

Douglas Lipton’s substantial new collection, An Enclave in Eden, opens with both feet very much in Edwin Muir’s ‘other land’ and not in Eden. ‘A Grandchild Sings’ uses the form of a child’s litany to catalogue a sense of world-wrong and impending catastrophe: ‘the beaches are heavy with whales/and the air is bouncing with flies.’ Our troubled covenant with nature is just about intact at the end as ‘Dolly is having a baby’ – indeed, it is what the baby is being born into, a fallen human condition and a ‘sullied’ environment, that is the main subject matter of this skilled and memorable book.

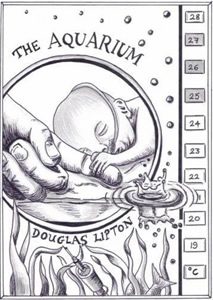

The suggestion of exposed creatures of the subconscious in the beached whales is returned to in ‘Allan’ and ‘Conger’ and more playfully in ‘The Slow Worms’ where Eden’s serpent , a ‘foot of cool muscle/with skin like magnesium’, keeps disappearing ‘into the sphagnum’ just as we attempt clumsy communication (as it did for D. H. Lawrence). Those depths are seen as healing as well as frightening in a number of poems, or at least they are depths that must be endured in order to survive the full range of the human condition. Those who have been there and back are archetypal guides, like the man from the funeral parlour in ‘Undertaking’, from the shorter collection, The Aquarium: ‘He has, however, a head for those depths. He has been down there before.’

Some of the poems in The Aquarium are as moving as any poems I have read on bereavement, as Lipton finds perfectly pitched expression for the grief of losing a new born child after three desperately short weeks of life in an incubator. There is terrible poignancy in the poem ‘Eyes’ as the baby’s voice is laden with the exhaustion of suffering: ‘I want to live, I think/but if this is how life keeps its word/then I am broken already.’

And afterward, as Hemingway said, many are strong in the broken places. For all the pain of the human condition in these books (Lipton is especially unflinching in the poems about childhood, an area where some poets return too easily to Eden) there is a great deal of hard-earned faith in life, as well as engaging warmth and anecdotal humour, which Lipton’s style of carefully phrased and lineated free verse is well suited to. In ‘White Bird’, the final poem of An Enclave in Eden, the poet is a modern day Adam who has seen a rarity, a white bird, and names it ‘Thorn Finch’, both ‘for its domain/in nature’s torture chambers/and for its plumage/like flowers of the sloe.’ Lipton’s imagery is a strength throughout: precise and often eidetic, reminiscent at times of MacCaig, but always weight-bearing, in ways which deepen the semantic possibilities and mystery of the subject.

These collections should firmly establish Lipton’s reputation as a significant voice among contemporary Scottish poets. He is a poet with no designs on the reader: this is a body of work you can trust and admire and be moved by, without at any time feeling that the real subject matter is the poet’s display of erudition (a flaw in too much contemporary poetry). These are the kind of poetry we need: they help us understand who we are, and just how much we are able to endure and enjoy east of Eden.